Coronavirus 2019nCoV Facts and Protective Clothing Selection Recommendations

With news reports now peppered on a daily basis with sometimes contradictory and often confusing reports regarding this latest virus outbreak, and with health services around the world gearing up to manage the seemingly inevitable cases that will emerge, this blog looks at the key facts as currently understood and suggests garment recommendations for healthcare workers involved in caring for infected patients

2019-nCoV emerged in the Chinese city of Wuhan in December and is the latest variant of the Coronavirus family – so named because of its structure which creates a star corona-like appearance. Others examples have included SARS which emerged in 2003, eventually spreading to 26 countries with 8098 known infections and 774 deaths, and MERS which came to light in the Middle East in 2012, resulting in 1180 known cases and 483 deaths. It is a Coronavirus that is responsible for the common cold, and different variations – including this one – result in similar symptoms – some worse than others.

The new Coronavirus was previously unknown so detail on it is still under investigation.

However, what is clear is that the latest evidence suggests this virus spreads very easily. It is primarily transmitted within moisture droplets resulting from coughs and sneezes. It appears that it can transmit during the incubation period of 1-2 weeks and before symptoms emerge, so spreading of the virus is highly likely and difficult to prevent. The virus can also survive on surfaces outside the body for some time, again increasing the likelihood of widespread infection.

Symptoms appear less severe than SARS – like other Coronaviruses it is primarily those with weakened immune systems or other health complications that are at real risk and many of those infected will develop symptoms similar to and no worse than a bad cold. The consequence of this however is that many of the infected may not present themselves at a hospital and will recover without the infection being recognised. Thus the actual number of infections is likely to be much higher than the officially recognised cases – again making control of widespread infection difficult.

At the time of writing (28 January) some 106 people have died and there are almost over 4500 known infections – mostly in China and other Asian countries, and with three in France and two in the USA (all traceable directly to Wuhan). However, given the points above the actual number of infections is likely to be much higher than this – unrecognised cases may already exist in many countries. In fact the UK’s Public Health Director stated on Monday (27th) that cases of infection within the UK are already likely if not yet identified.

It is evidence of the ease with which Coronavirus 2019-nCoV transmits that a number of health workers have already been infected despite the care they are used to taking with virulent infections. The important question therefor is how can health workers minimise the risk of infection when handling known cases of Coronavirus 2019-nCoV?

This means what protective clothing should be selected? Which garments are suitable for healthcare workers involved in the care of patients infected with Coronavirus 2019-nCoV?

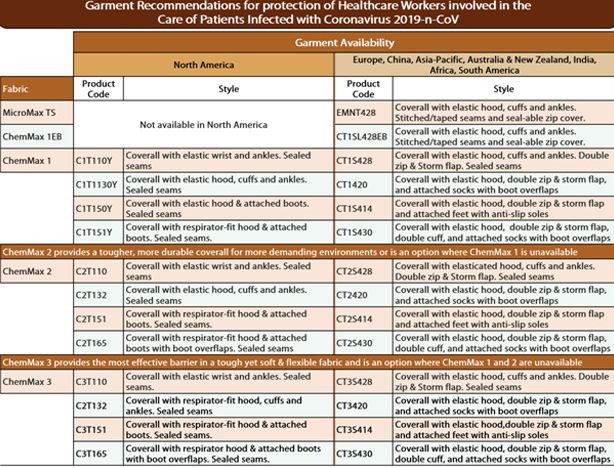

The garment recommendations are shown below. Weare a global supplier and for reasons of local standards, regulations and convention, availability and styles vary in each region.

The table details garment types and styles with product codes and brief descriptions available in the different regions. The general properties of each are detailed in the fabric option outlines below the table.

The garment recommendations are shown below. Weare a global supplier and for reasons of local standards, regulations and convention, availability and styles vary in each region.

The table details garment types and styles with product codes and brief descriptions available in the different regions. The general properties of each are detailed in the fabric option outlines below the table.

The garment recommendations are shown below. Weare a global supplier and for reasons of local standards, regulations and convention, availability and styles vary in each region.

- Fabric achieves high classes in the critical EN 14126 tests ISO 16604, EN 14126:Annex A and ISO 22611. A high classification in ISO 16604 is desirable.

- A garment design meeting the requirements of at least Type 4 as defined in EN 14605 which requires sealed seams and a seal-able zip cover.

On this basis the following garments are recommended:-

Fabric/Garment Option General Properties

MicroMax TS

(NOTE: MicroMax TS is NOT AVAILABLE IN NORTH AMERICA)

- Microporous film laminate achieving the highest class in all four tests in EN 14126

- Lightweight and flexible fabric for maximum comfort

- Sealed, stitched and taped seams and seal-able zip flap

- Lightweight and more comfortable garment for lower risk applications

ChemMax 1EB

(NOTE: ChemMax 1EB IS NOT AVAILABLE IN NORTH AMERICA)

- ChemMax 1 variant originally developed and used widely for the Ebola relief effort in Sierra Leone

- Barrier film achieving the highest class in all four tests in EN 14126

- Sealed, stitched and taped seams and seal-able zip flap

- ChemMax 1 garments might be selected for higher risk areas as the fabric is more robust than MicroMax TS and features an impervious barrier film. The EB version is the simpler, single zip design.

ChemMax 1

- See table for styles available in each region

- The standard ChemMax 1 Type 3 & 4 protective coverall

- Barrier film achieving the highest class in all four tests in EN 14126

- ChemMax 1 garments might be selected for higher risk areas as the fabric is more robust than MicroMax TS and features an impervious barrier film

ChemMax 2 andChemMax 3.

Both of these fabrics pass all EN 14126 tests with the highest class and are both Type 3 and 4 in EN 14605. The fabrics are tougher and more durable so may be suitable in more demanding environments and are options if MicroMax TS or ChemMax 1 products are not available.

Note that not all the styles detailed above are always available from local regional stocks at all times. For more information on garment options and availability contact your regional sales office. Contact details can be found here.

The criteria for the garment options offered are detailed below. A downloadable factsheet with outline garment options is also available here (available shortly).

What is the basis for Lakeland’s garment options above? What criteria have been used to determine which garments are suitable and which are not?

These guidelines provide good advice on the general management of healthcare environments including vital human behaviour components: key to control is regular and thorough washing of hands before and after any contact with an infected patient. However, whilst specifying the use of a “long-sleeved gown”*, in many cases where risk is higher a coverall will be required – and indeed many of the enquiries Lakeland is already receiving are for coveralls and not gowns. In either case, despite the wide choice of disposable garments using a variety of fabrics available, the WHO guidelines make no mention of the type of fabric that should be selected.

The selection criteria relate to two issues:-

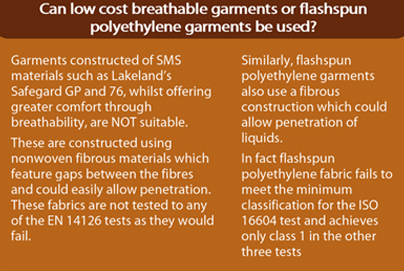

- The Fabric Choice – which fabrics are suitable and will provide adequate resistance against penetration of contaminants

- The Garment Design Choice – which garment style will minimise the risk of penetration inside the garments

Each of these is considered in the light of the known routes of contamination for the virus.

FABRIC CHOICE

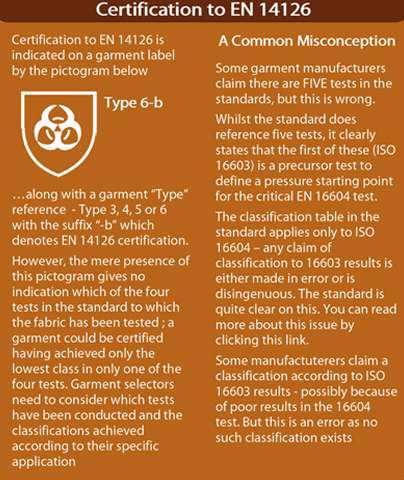

The Critical EN Standard

Fortunately an EN standard provides excellent guidance for fabric choice. EN 14126 comprises four critical tests to assess the effectiveness of resistance to penetration by infective agents of a coverall or gown fabric.

Each test assesses resistance to different types of contamination routes:-

- ISO 16604: liquids under pressure (ie, body fluids),

- EN 14126:Annex A: mechanical contact with contaminated substances

- ISO 22611: penetration by contaminated liquid aerosols

- ISO 22612: penetration by contaminated solid particles

The four tests, along with the classification tables are detailed in the table below:-

The main routes of transmission for Coronavirus 2019-nCoV are as follows:-

- Transmission in contaminated airborne droplets resulting from coughs and sneezes

- Close personal contact (this could include touching of skin as a result of shaking hands etc)

- Touching an object (such as a door handle or bed rail) that is contaminated

- Faecal contamination (rarer – but obviously a possible issue in healthcare of the worst affected patients)

Considering these routs of contamination the critical tests within EN 14126 are:-

- ISO 16604: Resistance against liquids under pressure (ie, body fluids) Sometimes necessary close contact with patients may result in direct contact with fluid droplets from coughs and sneezes

- EN 14126:Annex A: resistance against mechanical contact with contaminated substances Surfaces in the immediate environment are likely to become contaminated and present a risk. (for example leaning against the railing of an infected bed rail )

- ISO 2261: Resistance against penetration by contaminated liquid aerosols Coughs and sneezes create a contagious aerosol of contaminated liquid droplets

Thus any selection of garment fabric should as a minimum achieve high classes in each of these three tests.

Of these the EN 16604 test is commonly considered the most important because it uses a synthetic blood infected with a “bacteriophage” to assess penetration. Critically for this analysis, the bacteriophage used is a much smaller size than Coronavirus 2019-nCoV:-

Average size of bacteriophage used in ISO 16604 0.027 microns

Average size of Coronavirus 2019-nCoV 0.125 microns

Thus passing the ISO 16604 test at a high class is a good indicator that a fabric is unlikely to allow the virus to penetrate, regardless of the medium.

On this basis therefore, Lakeland’s suggested options for fabric choice are as follows:-

MicroMax TS

A Microporous film laminate material that whilst offering some limited breathability through moisture vapour transmission features excellent resistance to penetration by liquids and dusts. The fabric passes all four tests in EN 14126 achieving the highest class in each. This provides an excellent lightweight and more comfortable option for lower risk situations.

[Note: The difference between MicroMax NS and TS is essentially the seam type and that on TS the zip cover can be sealed with double-sided tape. The fabric is the same, but I have used the TS suffix here to avoid confusion].

Whilst the material in these garments is the same and meets these requirements we would not recommend the standard MicroMax NS coverall which features standard stitched seams and an un-sealed zip; stitched seams feature holes through which penetration can easily occur – especially as a result of the bellows effect which can actively draw airborne particles or droplets through seam holes. Thus we would always recommend the MicroMax TS coverall which features sealed seams and a sealed zip cover. (See “Type 4” garments below)

ChemMax 1,2 or 3.

These feature fabrics primarily designed for hazardous chemical protection and thus feature solid barrier films providing maximum protection against ingress. Each is tested to all four tests in EN 14126 and achieves the highest class in each thus meeting the fabric requirements.

The lightest weight option is ChemMax 1, whilst ChemMax 2 and 3 would provide tougher, more durable options for any more demanding or strenuous environment.

GARMENT DESIGN CHOICE

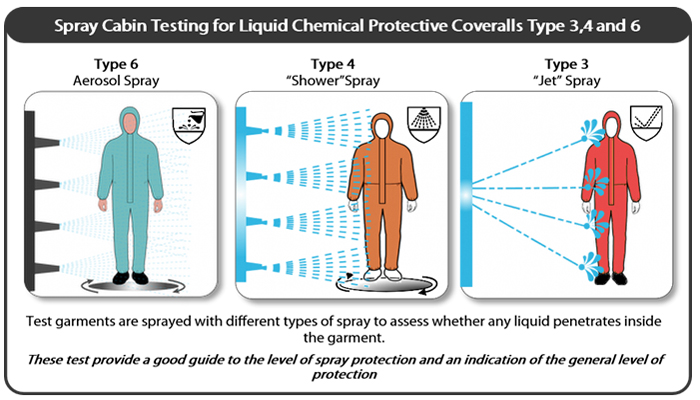

Garment design of protective clothing against liquids and dusts is defined in several EN standards. These standards use a finished garment spray test to assess penetration inside the suit under different types of liquid spray. These are described in the panel below:-

The most common is Type 6 – the lowest level of liquid protection. However, we would not recommend this as it requires only standard stitched seams which feature stitch holes and so could allow penetration.

Type 4 garments however require both sealed seams to prevent any penetration of liquids through the seams and that the zip cover can be sealed, preventing penetration through the zip teeth and backing material.

Thus our recommendation for garment design is at least a Type 4 garment, ensuring minimal likelihood of penetration through seams and fastenings.

You can download an essential factsheet with garment recommendations on Coronavirus 2019-nCoV here.

You can also learn more about protective clothing issues, whether you’re interest in industrial, chemical or medical issues and application, by signing up to our blog

Leave a Reply